Take It Easy Carsten Tabel

Five to seven already. Alice was running late. She slipped into the yellow dress that Adam had brought for her from Detroit and put a stick of chewing gum in her mouth. She was tired and hung over. She’d sat by the bar at the bowling alley for three hours last night, letting men buy her drinks and occasionally whispering a few words to one of them. When she wanted to leave the house, she ran into Adam. She hadn’t even noticed when he’d gotten up. They’d fought, and he’d slept on the couch.

Where are you going?

He wanted to talk to her about their fight. That idiotic fight over the letter. She didn’t have time for this. Dwight Tombley, with whom she’d made a date for this morning after her third martini, was surely already waiting for her. Let Adam get mad and run off. To Wyoming, to Texas, to Anacortes. She didn’t figure in his plans.

It was a quarter past seven by the time Alice parked the station wagon in the fishing club’s parking lot. Dwight was busy hefting an enormous catfish into the trunk of his car and laboriously wrapping it in plastic foil. He wiped his hands on an oil-stained rag, turned around, and waved in Alice’s direction. He’d saved up one hundred and fifteen dollars behind his wife’s back. Alice sighed and got out of the car.

Tonight she’d tell Adam to get the fuck lost. She didn’t need his money.

Adam had found the letter to the Anacortes Music Channel in the glove compartment. He’d confronted Alice, enraged, and held it up to her face.

Shit, I forgot.

It had been three days since he’d made her promise to mail the letter. When he’d asked whether she’d been to the post office, she’d said yes. She apologized, but Adam didn’t believe her.

Who knows what you’ve done with the other applications.

He’d sent out eight letters over the past three weeks. So far he hadn’t received a single reply.

Chill, Alice had said, the world’s not going to end if it gets there a day later. I’ll drive to the post office right away.

But Adam had taken the envelope, torn it to pieces, and asked: Are you happy now?

Oh Alice, that was just fantastic.

They were sitting in the back seat of the station wagon and smoking. Dwight reached for her hand.

Keep your fishy hands off me, Dwight. That was it for today. Got it?

It wouldn’t hurt if you were a litter nicer.

Alice stubbed out the cigarette and wanted to open the door, but Dwight held her down.

Alice, baby …

She tried to extricate her wrist from Dwight’s grip, but Dwight was stronger.

I want to give you the fish as a present.

You must be off your rocker, keep your ugly fish and let go of me.

But Dwight didn’t let go.

Who’s ugly, you little cunt?

As he hurled abuses at her, she lugged the catfish, which weighed well over forty pounds, from his trunk into hers and drove off. Ten minutes later, to her own surprise, Alice suddenly started sobbing. The unexpectedly vigorous piston-fucking she’d gotten from Dwight and then the humiliating insistence with which he’d forced his “greatest catch in twenty years” on her seemed to have shaken her more deeply than she’d thought.

The chewing gum she’d kept in her mouth, ignoring Dwight’s protestations, slid into her windpipe. Tears had clouded her vision, now she also started coughing and panicking that she’d choke to death, and Alice’s station wagon veered off Rural Road 651. A vestigial reflex asserted itself. Alice stepped on the brake, setting the fish in motion. It rose from the trunk, hurtled toward the windshield, and, along the way, slapped Alice’s right temple with its tailfin. Even before the fish crashed through the windshield and departed the car, Alice was unconscious and collapsing into the driver’s seat.

When she woke up six hours later in the intensive care unit of the hospital to which she’d been taken by a medical helicopter, she was asked her name. She shook her head. She gave the same response to the questions for her age, relatives, where she worked. The only question she answered without hesitation was where she lived. Anacortes, Washington.

Adam was waiting for Alice. He’d bought two bottles of wine and frozen pizza. A reply from a local station in Texas had been in the mail. He’d gotten the position. Finally a steady job, no more traveling, no more hotel rooms, no more movie sets. He’d be on the road tomorrow, and he’d take Alice along. He’d met her two years ago, when they were shooting at the bowling alley where she cleaned the bathrooms and helped out behind the bar. They’d sat at the bar after her shift and she’d told him that she was new in town and that he was the first good-looking man she’d met. Then she’d taken him to her small house outside of town. Back in L.A., he’d given notice on his apartment in Silver Lake, packed his suitcases, and driven back to Alice’s place.

With my job, it doesn’t matter where I live. I’m on the road half of the year anyway. I want to be with you when I come home. I’ll pay the rent.

Alice had agreed.

At the junkyard, they’d found Alice’s driver’s license under the car mat on the passenger side. This answered the questions about her age, name, and date of birth. Ten days later, her parents had been located.

Alice’s father didn’t quite get what the policeman on the phone wanted from him. Alice was the only one of his four kids who seemed to have a handle on her own life. She even survived accidents.

Her memory’s going to come back. Give her my love. Goodbye.

Alice’s mother was under the influence of mood elevators and Californian red wine when she promised the officer on the phone to come right away. Affected by her own solicitude, she said she’d take Alice in, no question. She packed her bag. Chunky, her boyfriend, who was thirteen years her junior, asked how she was going to pay for the trip and where she thought she’d put her daughter up in this dump. He asked whether she had shit for brains.

Alice had lived with her parents, two parrots, and a little white terrier in a suburb of Houston until she was five. Alice and her mother were on their way to the Unitarian church’s playgroup when her father’s car pulled up to them. He was pale and soaked with sweat. Trying to seem calm, he asked his wife and kid to get in. Alice, who’d lost her first incisor the day before, protested. She was looking forward to spending the dollar she’d found under her pillow the next morning on a luminous blue popsicle on a chewing gum stick. Shut up and get in the car, daddy whispered in her ear. They drove home, Alice was furious, she cried.

You wait, her parents instructed her when the car stopped in front of the white house not far from the beach. Alice was obedient and stayed in the car. Father and mother disappeared into the house and quickly gathered valuables and clothes. They released the parrots, and after a quick debate Alice’s mother killed the dog. Alice flinched when she heard the gunshot. Her parents came rushing from the house dragging plastic bags and suitcases. Daddy was crying. For the next two weeks, they were on the run from evil men who wanted to hurt daddy. For two weeks, the three of them slept in the car, subsisting on potato chips and gas-station hot dogs. Mommy asked what was to become of them. Daddy didn’t know. And then daddy was gone.

It was past midnight and Alice still wasn’t home. Adam had finished off a bottle of wine and was trying to maneuver his thoughts and feelings between concern, elated anticipation, and disappointment. He just hoped that nothing had happened to her. He’d get her a new car in Houston, with seat-belts, airbags, and other safety gimmickry. He’d rent a house, perhaps even buy one, who knows, maybe he could get Alice a job with the station as well. He’d called Jim. They could stay at his place until they’d found something, no problem.

Alice, no registered address, no permanent residence, stood outside the hospital, one hundred and fifteen dollars in her wallet, three envelopes in her hand. No one had come to pick her up.

One of the envelopes contained her discharge paperwork, the other two were from an insurance company. With amnestic syndrome patients, the hospital’s billing department routinely contacted the major insurance companies. When someone had lost their memory, they also didn’t know whether they had health insurance and with which carrier. The administrators hardly expected a reply, and so they were enormously pleased when a letter from the Nationwide Insurance Company confirmed that it would cover all expenses. Alice’s father had taken out the personal accident insurance soon after she’d been born and opened an account in her name with the Texas Credit Group into which he paid fifty dollars every month and from which the quarterly insurance premiums were deducted. A few months before the family absconded from Houston, he’d been forced to cancel the monthly payment into Alice’s account. He’d used up all his savings, his accounts had been garnished. He’d let himself get tangled up in something, or so Alice was later told.

Yet the insurance company had continued to collect the premium payments on schedule. The money came from Alice’s grandmother, who’d wired a five-figure sum into her account two months after Alice had been catapulted from her Texan childhood. A loan shark breathing down his neck, Alice’s father turned to his mother for help. He was unable to get her on the phone. On a whim, she’d sold her house in Des Moines and moved to Florida with a girlfriend without letting anyone in the family know. In his despair, Alice’s father picked up pen and paper and candidly confessed to the straits he was in. Thanks to a change-of-address order on file the United States Postal Service, the letter arrived in Florida, though it took six weeks. His mother got into a cab, went to the bank, and had the requested sum transferred. But by this time her son and his little family were already on the run and had vanished from her life forever.

Alice sat down on a bench in the park outside the hospital and examined the two letters addressed to her. The first informed her that her hospital bill would be covered and the contractually stipulated sum of 438,000 dollars would be paid out into her account with the Texas Credit Group. The other envelope contained the policy cancellation notice from the insurance company.

If she didn’t feel like a desk job with the station, Alice might work at Jim’s bar. Adam was making progress on the second bottle of wine. He knew Jim from one of his first television jobs, a reportage titled “America’s Most Disgusting Artists.” They’d filmed him as he’d forced down an enormous jar of mayonnaise only to puke it all back up. Afterwards, in the interview, Jim had said:

I feel blessed that I can have faith that I’m free.

Adam had often pondered this statement, but to this day he hadn’t figured out how mayonnaise was supposed to be connected to freedom and faith.

Yes, Alice would love Jim and his crazy bar. But Alice didn’t show up, and the longer Adam waited, the more he took her staying out to be a signal of rejection. He downed the rest of the bottle. Why should she go away with him? In her life, everything was fine just as it was. When he was on the road, she was free to do as she pleased, bar-hopping and bed-hopping without him knowing about it. When he was with her, he behaved like a generous guest, took her out to dinner, bought her dresses and shoes. But he’d had it with her. At three in the morning, Adam put his things in the car. He sat motionless in the driver’s seat for another two hours before starting the engine and driving off to Texas.

Thanks, Alice said, and stuffed the change back into the leather neck pouch she’d just bought, which she promptly slid back underneath the blue-and-green knit sweater with the cat motif. She’d laughed out loud when she’d spotted the sweater in the bargain bin at the thrift store. The cat was a black and red striped specimen, plump and shapeless. A speech bubble coming out of its ear read: “Take it easy.”

She asked the cashier for the easiest way to get to Anacortes.

The woman behind the counter frowned.

That’s in Washington State.

It was ten in the evening by the time Adam got to Houston. Along the way, he’d tried several times to call Alice.

He found Jim on the third floor, lying on the couch and doodling in a notebook.

Where’s your girl? Jim asked.

Adam shrugged.

Let’s go downstairs.

Jim got something from the bar. Adam looked around.

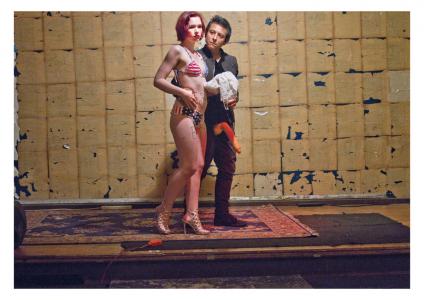

On the stage, a woman in a stars-and-stripes bikini was peeing on a photograph of the president. They were all here. The homeless, fashion models, artists, skin girls and Japanese punks, glittering people and chess players.

When Jim was nine, he’d hated school so much that he’d trained himself to throw up whenever he felt like it. Every morning, when the class had recited the Pledge of Allegiance, Jim had puked into the wastebasket. They’d sent him to the school nurse, who’d sent him home. Jim would later say about his puke performances: My primary goal is to help the nine-year-old-boy inside me not to injure myself and to speak up and become an emotionally mature grownup.

The editor asked Jim why he didn’t just go into therapy. Jim responded by barfing on her shoes.

Adam remembered the bar as a magical scene. Now that he was here he felt out of place. The older men at the bar at the bowling alley where Alice sometimes helped out would slip her absurdly large tips, but this was different. He tried to imagine Alice behind the bar. He wasn’t sure that he still liked it here. Jim poured them vodkas.

To freedom.

He’d call Alice right the next morning. He’d pay for her flight and have her join him. But not until he’d found a house. No, he wouldn’t have her sleep on a dirty mattress in a corner at Jim’s place. She deserved better.

Poor thing, the lady behind the counter at the Greyhound bus station thought. The young woman in the cat sweater whom she’d just sold a ticket sat by gate number five, licking a popsicle that tinged her tongue blue, grinning and talking to herself. Poor thing has lost her mind. Well. At least she’s off to the West Coast, where the other crazies live. They’ll take care of her.

Alice, however, couldn’t have been happier at that instant. Her surroundings had no power over the paradisiacal images in her head. She didn’t notice the poverty of her fellow bus passengers, seeing herself in a house by a beach, surrounded by friends. She smelled these friends’ freshly bathed bodies, heard their voices, heard them say her name.

No unpleasant feeling penetrated her consciousness. No recollection of the humiliating moves by bus, the raw nerves, of father or mother. Always on the run. From landlords, employers, tax collectors, and above all from themselves. No recollection of the trauma of failure. Dwight’s fish had slapped it all out of her head. Alice was buoyed by the irrepressible thrill of anticipation and her lust for life. She would be home soon. In no more than two days, she’d be back by the sea, finally. She already felt the surf lapping at her feet. She saw palm trees, turquoise waters, felt the heat, saw herself going for a stroll along the beach with a little white dog. She saw herself with a man on the roof of the Empire State Building, saw herself kissing passionately on the Eiffel Tower. Someone in Anacortes was waiting for her. Alice blushed, and she emitted a soft cry of joy.

It was a happy life she was coming back to, and all of Anacortes was expecting her.

Translation by Gerrit Jackson